We’ve always been told to wash our hands. It’s considered to be the single most effective way to minimize or even prevent the spread of infections (1).

As nurses, our exposure to sickness and infections is much higher than regular folks. Let’s make sure we’re following proper procedure on hand washing.

Here’s a guide on proper hand washing for nurses.

What Hand Washing Means

Hand washing means cleaning your hands with any liquid to remove dirt and microorganisms. It falls under hand hygiene which is a general term that applies also to surgical hand antisepsis and antiseptic hand rub.

Surgical hand antisepsis is what most healthcare workers know as surgical hand scrub. It’s generally done to remove as many microorganisms as possible from your hands before doing any surgical procedure.

Antiseptic handwash, on the other hand, means washing the hands with antimicrobial soap and water.

When to Perform Hand Hygiene

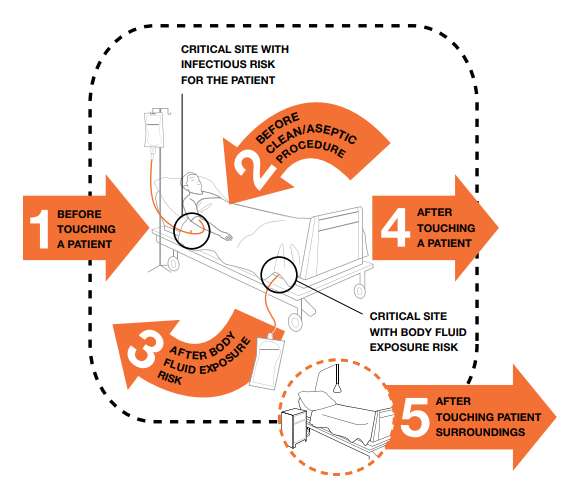

Based on the guidelines of the World Health Organization, there are five moments for hand hygiene.

You need to perform it:

1. Before touching a patient- before shaking hands, assisting in personal care activities, delivering care, performing physical non-invasive examination

2. Before performing a clean/antiseptic procedure– before dressing a wound, instilling eye drops, inserting a nasogastric tube, preparing food

3. After getting exposed to body fluids– after inserting invasive medical devices, handling samples with organic matter

4. After touching a patient– after shaking hands, changing bed linens, taking blood pressure

5. After touching a patient’s surroundings– after a care activity, clearing a patient’s bedside table

Proper Hand Washing Procedure for Nurses

Things you’ll need:

- Warm running water

- Soap

- Paper towels

Steps:

1. Thoroughly wet your hands and apply soap all over your hands’ surfaces.

2. Rub your hands together (palm to palm) to create a lather.

3. Place your right palm over your left dorsum and interlace fingers to clean the area. Then, place left palm over the right dorsum and do the same thing.

4. Next, rub palm to palm with your fingers interlaced.

5. Don’t forget the backs of your fingers. Clean the area using the opposing palm with your fingers bent and interlocked.

6. Rub your thumb with opposing palm. Do it on both thumbs.

7. Rub clasped fingers using backward, forward, rotational movements on your right palm and vice versa.

8. Rinse your hands with water.

9. Dry your hands with a single-use towel.

10, Turn off the faucet using the towel.

If the instructions aren’t clear, here’s a video showing proper hand washing:

Note: The entire hand washing procedure should take around 40 to 60 seconds.

What If You Can’t Wash Your Hands?

In case you don’t have access to water or a sink, you have the option to use an antibacterial hand sanitizer. Just remember to use one with at least 60% alcohol and use a lot of it. Although it won’t be able to remove visible dirt, it can help prevent the spread of bacteria and germs.

In using hand sanitizers, keep in mind that they work best when there’s enough to lightly coat both of your hands. It needs to dry completely to work.

In using a hand sanitizer, here are the steps you should follow:

1. Take a palmful of hand sanitizer and completely cover the surfaces of your hands.

2. Then, rub your hands palm to palm.

3. Rub your left palm up and down the back of the other hand with interlaced fingers and vice versa.

4. Next, rub palm to palm with interlaced fingers.

5. Also, rub the backs of your fingers on opposing palms with interlocked and bent fingers.

6. Rub the thumb clasped in the opposing palm and vice versa.

7. Rub clasped fingers in a rotational, backward, and forward direction in opposing hand.

8. Consider hands clean once dry.

Note: The process should take 20 to 30 seconds.

To give you a clearer idea, here’s a video showing the proper way to do a handrub.

Hand sanitizers can’t always be used as an alternative to hand washing. If you see that your hands are visibly dirty, you’ll need to wash your hands with soap and water.

Hand washing with soap and water is also needed if you are caring for patients with clostridium difficile, cryptosporidium, and norovirus. Additionally, you should also wash your hands:

- after a known or suspected exposure to patients diagnosed with infectious diarrhea

- after using a restroom

- before eating

- if there’s suspected or proven exposure to Bacillus anthracis or anthrax

Proper Skincare After Hand Hygiene

Frequent hand washing and hand hygiene can leave your skin dry and irritated. In some cases, it can even lead to contact dermatitis. The condition is marked by scaling, redness, itching, swelling, cracking, weeping, and pain.

To reduce your risk of having work-related dermatitis, consider using machinery and tools instead of your hands. If you have equipment cleaning machines in your area, use them.

When washing your hands, completely rinse off residual cleanser and soap. Make sure that your hands are thoroughly dry before getting back to work.

Try to use emollient hand creams, particularly after your shift. Remember to completely cover your hands with the product.

Assess your skin for early signs of skin problems so you’ll be able to treat them as early as possible. If you see any wounds, cover them with a waterproof dressing.

About Your Fingernails

As much as possible, keep your fingernails short. Long fingernails tend to harbor bacteria and germs which you can easily pass along to your co-workers and patients.

Whether you have artificial or natural nails, keep them to about 1/4 inch in length. If you can have shorter nails than that, the better.

In case you are assigned to care for high-risk patients, don’t wear artificial nails. They are believed to carry more bacteria (2).

Artificial nails are also associated with poor hand washing practices and more tears in gloves (3).

References:

- Mathur, P. (2011). Hand hygiene: back to the basics of infection control. The Indian journal of medical research, 134(5), 611.

- Pottinger, J., Burns, S., & Menske, C. (1989). Bacterial carriage by artificial versus natural nails. American Journal of Infection Control, 17(6), 340-344.

- Toles, A. (2002). Artificial nails: are they putting patients at risk? A review of the research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 19(5), 164-171.